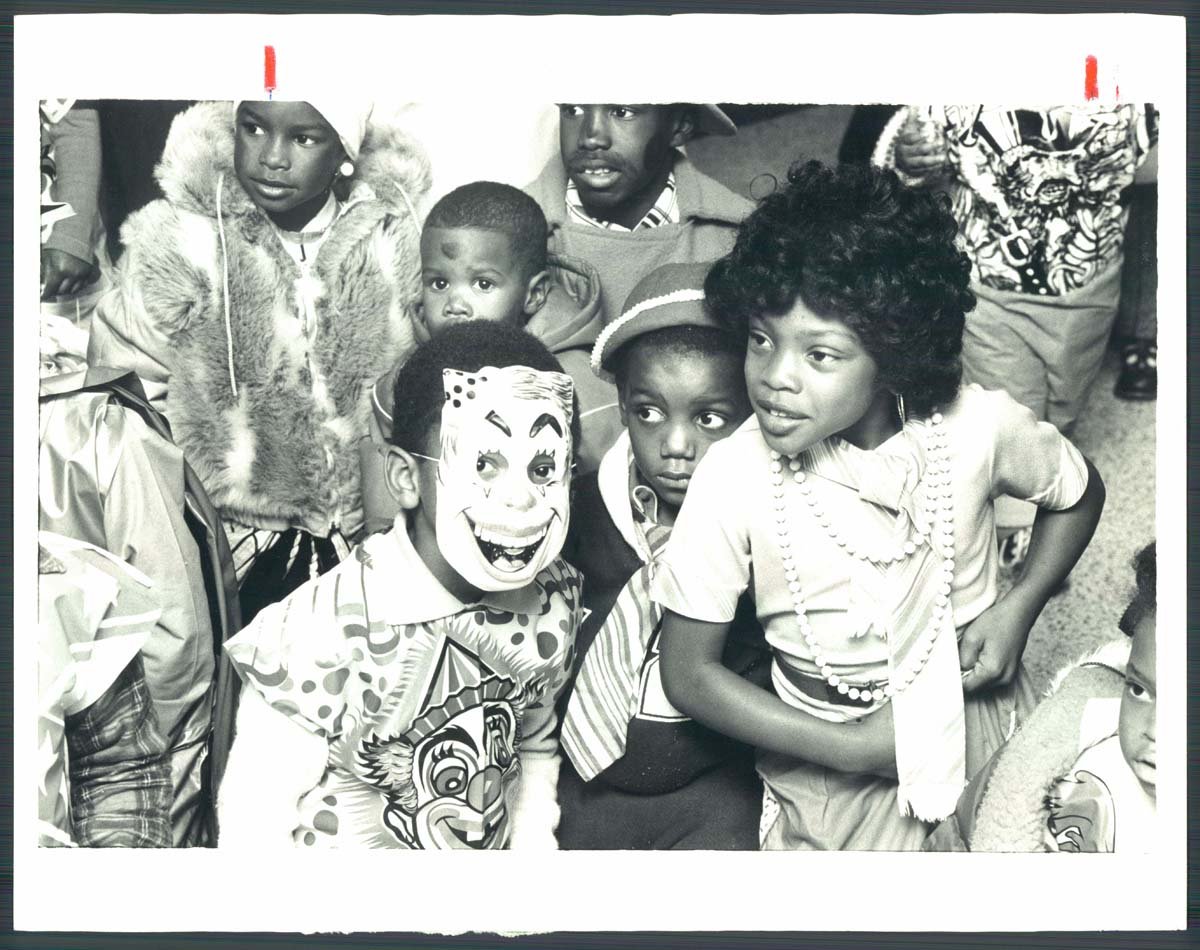

On Halloween

Halloween scene in 1981. (Weyman Swagger/Baltimore Sun)

A lot of people remember Halloween as one of the earliest memories of their childhood. From dressing up in one’s favorite costume and getting your favorite piece of candy to being absolutely terrified, the ways in which people celebrate or don’t celebrate Halloween gives us some insight on people’s relationships with traditions and holidays.

According to religious leader Bishop Joseph Howze (1923 - 2019), Halloween had different origins in comparison to how it is commonly celebrated today:

“...Halloween is really the eve of the hallowed, the eve of the saints…It was supposed to be something of that nature, but it has really changed its structure of a lot of ways. For instance, I heard the other day, why jack-o-lanterns were a part of Halloween, was that in Ireland, they had the idea that there was man once who was rejected by both God and the devil at the same time…and one of the things that he had to carry a lantern with him everywhere he went. So this is the idea of how jack-o-lanterns got into the idea of Halloween…Halloween was really the eve of the feast of All Saints, a great feast day, celebrating the sainthood of everybody because there are many saints who are not canonized by the Catholic church, but they're still saints. And so the church has its feast of celebrating that. But you get a feast like Halloween which is really agonized, the whole celebration and it's, it's not what it used to be” [1].

Halloween, amongst other holidays, is also a big-deal in some households. According to Amy S. Hilliard (1952 - ), marketing executive, founder and CEO of the Comfort Cake Company:

“Oh, goodness, holidays were really special. My parents made a big deal out of holidays, particularly Thanksgiving and Christmas. Halloween was a big holiday because my sister Pam's birthday was October 27, and so it was always close to Halloween. So her birthday party was always fun, because we always celebrated Halloween together, and we always had pumpkins at the tables, and we could dress up for Halloween” [2].

For Nonprofit administrator and foundation executive, and an advocate of civil rights, HIV/AIDS awareness and the arts, Cleo F. Wilson (1943 - ), recalls Halloween to be one of the ‘sights’ of her childhood:

“I think that the Halloween thing I described, I think that's a sight. I don't know, I have to think about the sounds. Smells, the cedar chips I guess. Whatever kind of chips that they put on the playground. I can remember that smell. I don't know what kind of chips it is though, some wood chips of some kind” [3].

Growing up on 63rd Street in Chicago, Illinois, Art collector and curator, co-founder of Diasporal Rhythms, a not-for-profit arts organization that promotes the collection of contemporary art works by artists of African descent, Patric McCoy (1946 - ) remembers Halloween as a very special time for him and his neighborhood because he lived in a strong community where everyone knew each other, and there was no need to worry too much about the safety of children going out alone on Halloween night:

“Everybody knew everybody on the block. It was…a village. And, you know, my mother…was a pretty strict disciplinarian, and she could instill the fear of God in you, but very loving. And so, when she told us that we could not walk across the street, we could not cross the street--we was little kids. So, our world was that block where you could go all the way around the block, but never cross the street, and that was our world…Everybody knew all of the vendors. And on Halloween, we would, we knew everybody on the block, so…the kids would…be able to go by ourselves 'cause there was, there was no fear 'cause everybody knew everybody, you know, it was. And I think about it today…how much children miss from not being raised in a community where all of the adults looked after them, and, and to a point that you could give them one night where they could just run crazy, you know. And nobody was going to hurt them, you know, 'cause Halloween was a really, really, really special time for us when we could run the street…in our costumes and unescorted, you know…It was a wonderful experience in that neighborhood. Ican look back on it now and, and really feel very blessed” [4].

Community also played a big role in police officers and city government administrators and as a police chief of Albion, Michigan and Windsor, Connecticut, Maxie L. Patterson (1944 - )’s depiction of Halloween. Growing up in a tight-knit community like Patric McCoy (1946 - ), Patterson recalls Halloween as another safe and joyous time in his neighborhood to be celebrated:

“...I can remember Halloween when we used to go out trick or treating, and it was safe enough you could walk the streets and parents didn't have to go with you, and it was so entirely different in those days where it was really a festive occasion. And we would have these big brown paper shopping bags, and people gave you so much that you could fill them up, bring them home, drop it off and get another bag, and go back out, but you had to be careful because they would give you fruit, and the apples--apples and oranges were big, and so they would weigh the bag down, and sometimes they would split out the bottom. But also, a lot of times, you would go to a house and they have a big tub of water in there, and apples would be floating in there, and you had to get on your hands and knees with no hands, and get the apple out with just your teeth. And so…I have positive, fond memories” [5].

Radio personality for WNOV radio in Milwaukee, where she showcased rhythm and blues songs, La Donna Tittle (1949-) also shares fond memories of Halloween:

“...One of the greatest and most fun times living in Robert Taylor was the sense of community. You had all your friends in one building; you could go visit. You didn't have to worry about walking out in the street at night, getting hit in the head. You could go up the elevator, up the steps, down the steps, without having your mother wonder where you are. If you did something wrong, somebody else's parents would tell your parents, you know, if something was wrong. And Halloween, Halloween was the best time. Because you had--there are sixteen apartments on one floor, and you have sixteen floors. So, multiply that with the candy you pick up for Halloween is tremendous. We would be sick as dogs, because we'd eat candy for two weeks. You didn't have people checking your apples to see if razor blades was in it. You didn't have people checking your candy” [6].

Other initiatives like Halloween parades, were used to support the community by keeping kids in organized activities. Telecommunications lawyer Tyrone Brown (1942 - ), appointed by former President Jimmy Carter to serve on the Federal Communications Commission, remembers a Pumpkin Parade from his childhood:

“...We had something called a Pumpkin Parade on Halloween and the whole idea was to keep the kids off, off the street in disorganized activity and put them in organized activity. And so…through the local school and the local merchants, we built floats and the kids marched all around the neighborhood on, on Halloween and wound up in the local armory, where they had, you know, food and drinks and everything for families” [7].

In direct contrast to both McCoy and Patterson’s recollections of the role of community in the celebration of Halloween, Civic leader, wife of former Ambassador Andrew Young, and the vice chairperson of the Andrew J. Young Foundation, Carolyn Young (1944 - ), celebrated Halloween in a way that accounted for the lack of trust her grandmother instilled in her community:

“...When…Halloween would come, my grandmamma--I would dress up as a gypsy or witch--a queen. But, I had to sit on the porch and my brother would go out and trick or treat and bring me trick or treats. She wouldn't let me mix with the other kids… She said, ‘Nah, I don't trust daddies or brothers in other folk's houses.’ So, a lot of parts of that I missed” [8].

However, for some, Halloween was not to be celebrated, some for more intentional reasons than others. Religion professor and minister, assistant professor of Christian Education at the Interdenominational Theological Seminary (ITC) in Atlanta, Reverend Dr. Maisha Handy (1968 - ), did not participate in Halloween growing up because it was a holiday that was considered by her family to be “iconoclastic, [9]” which was in direct opposition of the Black Arts Movement that emphasized creating one’s authentic kinds of celebration:

“My mother would actually keep me home from school on Halloween, so I never--for a couple of years there, I didn't put on any costuming...I don't know if it was perceived as a Christian holiday, or if it was attached with some form of paganism. I'm really not sure what the situation was with Halloween, but I just know that we did not celebrate any of the kind of national recognized holidays like Thanksgiving and Christmas, Halloween, any of that…because they were in a kind of iconoclastic movement. was the intention of the whole Black Arts [Movement] and Black Power Movement is to create our own kind of Afrocentric celebrations, holidays, et cetera. So I think the whole purpose was to not participate in what the mainstream society was doing… for the empowerment of black people to restore a sense of the African self, African identity” [10].

For others like Education administrator and historical researcher, D.C. Public School elementary resource teacher coordinator of the Title I program, and curriculum developer in reading and language arts, Barbara Dodson Walker (1930 - ), Halloween wasn’t celebrated simply because she did not like to be frightened:

“…I never liked Halloween, and I never liked the 4th of July. I don't like to be frightened so I never liked those two and if they never had Halloween and the 4th of July, it would be fine with me” [11].

Lastly, Halloween was a lot scarier for some than others. For Loann Honesty King (1940 - ), Program administrator and educator, Consultant for the Department of Education, and as the Associate Director of Jobs at Youth Chicago, she can recall something truly scary. During elementary school, in the seventh grade, she was disturbingly told by on her teachers that her shamrock costume was not allowed and that she should not wear it back to school:

“…The biggest racist thing that I do remember was a Halloween, I guess I must have been seventh grade. O'Bryan [ph.] was here name, now that it comes to me, that was her name. I do remember for, my mother had gone and gotten me this wonderful costume which I thought was costume, 'cause I was always her little baby doll or whatever, whatever and it was a shamrock and it had a green shamrock oilcloth, hat, this pretty white kind of organza dress with little shamrocks on it and whatever, whatever. And so she dressed me up in this and of course and that's what I wore and we had to wear our costumes to school on a particular day and I remember her telling me that I could not be a shamrock, and I said to her why could I not be a shamrock? She said, "You cannot be a shamrock, do not wear that costume back to school." So, when we went home to lunch…I didn't want to tell my mother what she had said, but I knew she had said, "Don't wear it back." So, what I did was my mother had a little thing where we were--all the friends dunking for apples, so I deliberately plunged my whole side down into the, to dunk for the apple so that the costume would get wet and I couldn't wear it back” [12].

It is clear to see that Halloween is a different occurrence for everyone. Some choose to focus on and remember its importance in a religious aspect, to celebrate it as a holiday with family and community, or to simply not celebrate it for personal reasons. Exploring some of these stories gives us some understanding of Halloween is regarded currently and how it will be regarded in the future.

Search terms:

Halloween: 155 stories

Pumpkin: 47

References

1 Bishop Joseph Howze (The HistoryMakers A2002.201), interviewed by Larry Crowe, November 12, 2002, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 3, story 4, Joseph Howze talks about voodoo and its use of the Catholic canon.

2 Amy S. Hilliard (The HistoryMakers A2008.082), interviewed by Denise Gines, July 14, 2008, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 3, story 1, Amy S. Hilliard remembers the holidays.

3 Cleo F. Wilson (The HistoryMakers A2010.100), interviewed by Larry Crowe, August 25, 2010, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 1, story 13, Cleo F. Wilson describes the sights, sounds and smells of her childhood.

4 Patric McCoy (The HistoryMakers A2008.129), interviewed by Thomas Jefferson, November 7, 2008, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 2, story 3, Patric McCoy describes his childhood neighborhood in Chicago, Illinois.

5 Maxie L. Patterson (The HistoryMakers A2007.060), interviewed by Denise Gines, February 9, 2007, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 1, story 12, Maxie L. Patterson describes his neighborhood in Detroit, Michigan.

6 La Donna Tittle (The HistoryMakers A2003.041), interviewed by Larry Crowe, March 17, 2003, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 1, story 12, La Donna Tittle describes living in Robert Taylor Homes as a youth.

7 Tyrone Brown (The HistoryMakers A2012.062), interviewed by Larry Crowe, March 6, 2012, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 2, story 3, Tyrone Brown remembers migrating north to Orange Valley, New Jersey.

8 Carolyn Young (The HistoryMakers A2016.047), interviewed by Larry Crowe, October 4, 2016, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 2, story 3, Carolyn Young describes her experiences at Luther Judson Price High School in Atlanta, Georgia

9 Reverend Dr. Maisha Handy (The HistoryMakers A2005.200), interviewed by Larry Crowe, August 22, 2005, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 2, story 1, Reverend Dr. Maisha Handy describes her family's resistance to mainstream holidays.

10 Reverend Dr. Maisha Handy (The HistoryMakers A2005.200), interviewed by Larry Crowe, August 22, 2005, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 2, story 1, Reverend Dr. Maisha Handy describes her family's resistance to mainstream holidays.

11 Barbara Dodson Walker (The HistoryMakers A2004.015), interviewed by Sandra Ford Johnson, March 4, 2004, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 2, story 9, Barbara Dodson Walker talks about growing up in Washington, D.C.

12 Loann Honesty King (The HistoryMakers A2008.014), interviewed by Julieanna L. Richardson, May 28, 2008, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 2, tape 8, story 11, Loann Honesty King recalls discrimination from her elementary school teacher.