“Culture & Cornbread”: How Southern Cuisine and Dialect Represent Something Much Bigger

Source: Black Southern Belle Inc.

When thinking of cornbread, I am like most of the Black community and think of home, of family and as the song says of “Grandma’s hand” and the naiveness in me, thinks of the Southern cuisine as something very simple. Growing up in the South, having it as a reoccurring item on one’s menu, you forget greatly about the importance, history, and vitality of it all. You forget about what it meant to your ancestors, to your community, and conclusively to yourself. You forget that to most of the elder Southern community it was a means of survival, comfort, and of culture. In this blog, I explore “cornbread” in the Digital Archive and where it takes me is much more meaningful than just “Southern Cuisine”.

The culture of cornbread, though a Southern cuisine, is very widespread as it pertains to the Black community. Most of the stories I came across, even those who were born in the Northern area of the United States, included early memories of the reoccurring food item, its use, its taste and its power. “Cornbread” became routine as well as culture, where many of the childhood stories of these figures included a theme of resentment for the constant serving of cornbread. No one in the Black community could seemingly escape “cornbread”.

Paul Jones, a civic leader and art collector, who first attended school in the South, but was sent to New York to continue his education, in the Archive reminisces on his earlier memories of cornbread and its versatile uses within his childhood.

“You'd you have a nice, big, thick cake of cornbread made from grinding the meal that they'd gotten from the corn that they picked and put in shelter, and taken to the mill where they would take it--if you took a bushel of corn in, they'd take a peck of it and keep for themselves and grind the rest up for meal for you. Or if you're feeding your hogs, they'd grind it up in a different fashion for chops from the hogs. And then you'd go in and get a pot of butterbeans and cornbread and offer 'em sweetened water, which was nothing but a glass of water with sugar, no ice, no flavor, but it was a meal.”

- Paul Jones

Most of us within the contemporary culture only think of cornbread as a side or something that was just used within the context of a dinner, but to many, cornbread was everything and more.

Photographer Jason Miccolo Johnson, who was born in Hayti, Missouri but grew up in Memphis, Tennessee discussed the routine of his childhood and how it included cornbread.

“And every morning we had our routine of sweeping, dusting, and washing dishes, and cleaning up the kitchen, and then going and find something to, to cook, either putting on the beans, or starting the cornbread, or going out finding some wild berries, to come back and make our pies.”

- Jason Miccolo Johnson

Seeing the culture of Black children sweeping across generations, as a Historian, has been a very empowering experience for me, as I too remember picking berries during my childhood.

Cornbread is etched into the minds and memories of Black people. It represents more than a meal, it represents people, family, whether that be a mother, grandmother or even a teacher. To the Black community, it meant much more than a means of nutrition.

James Roberson, civil rights educator and engineer, was born and raised in Birminham, Alabama, an area infamous for the racial tension and violence of the Civil Rights Movement, recalls his mother discipline and how that included cornbread.

“She was a type of mother who prepared a meal every day. And she had a lot of rules in the house. And one rule was, whatever was placed on your plate had to be consumed by you. And I had a lot of problems with that because being a black child, I didn't like cornbread, and cornbread was a stable of blacks. Everybody ate cornbread that had soul.”

For many cornbread represented a discovery of one’s own culture and the deliciousness that it entailed.

Reverend Dr. Calvin Morris, born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, recalls his first encounter with skillet cornbread and its reoccuring and delectable counterpart collard greens.

“It was only when my father [Abner Williams] married my stepmom--I was 12 years old when that happened, that I really learned how delicious collard greens were and cornbread, and particularly the kind of cornbread that would be made from meal in a frying pan.”

- Reverend Dr. Calvin Morris

For others, the mention of cornbread brought up memories of a struggle and their community embraces them in ways they saw fit.

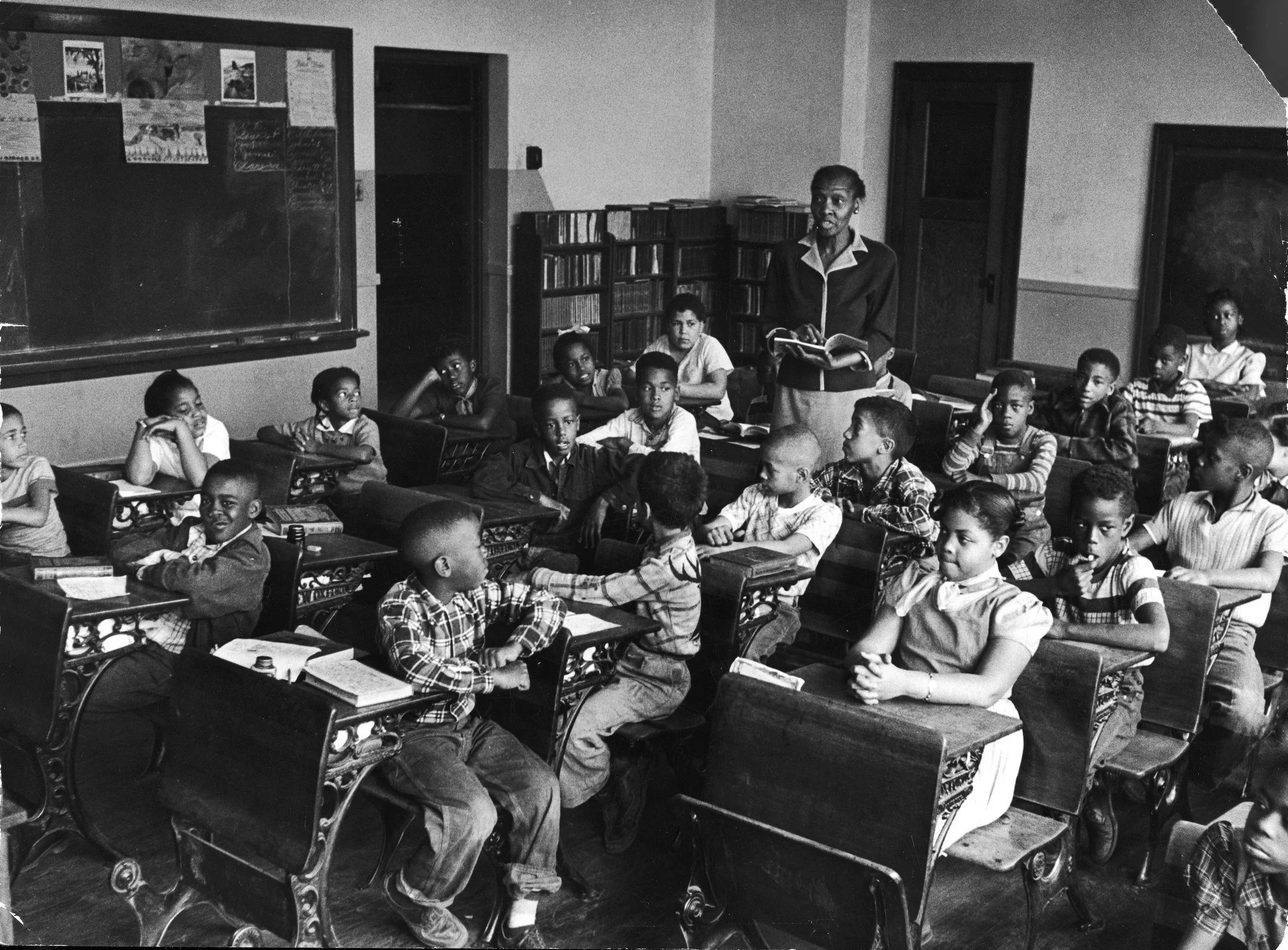

Reverend Dr. Arthur Rocker, Sr., civil rights activist, remembers how at a young age his favorite educators saw a need within him and satisfied it with cornbread.

“Mr. Harper [ph.], was, was a favorite teacher of mine, he, he, he was--he just taught me and he was nice to me because we, we couldn't afford lunch, and at that time they would send me down to eat pi- red beans and cornbread, and I would go down stairs to eat red beans and cornbread at school.”

- Reverend Dr. Arthur Rocker, Sr.

As I dived deeper into the Digital Archive, I came upon Ella Jenkins, a professional folk singer, who spoke of cornbread also:

“I love cornbread, and see when I was growing up we had cornbread--we had--my mother cooked real well. We drank buttermilk. I never hear people talk about buttermilk anymore, but we--and sometimes I put a glass of buttermilk and then I put some cornbread in it and stir it up, it would, tasted very good, and then we'd have chicken, fried chicken and then we'd eat cake along with it. You know, so there are just a lot of--and with black-eyed peas, and we--and then another thing I never hear, if you didn't have too much in the way of money--well you ate neck bones a lot. “

- Ella Jenkins

Though her story about cornbread was very endearing and familiar, what caught my attention was her recollection of the Black/Southern dialect. This mention definitely piqued my interest because as a Black woman and historian, I’ve always felt drawn to the history and value of AAVE ( African American Vernacular English/ Dialect) as it pertains to Black culture. When reading work by authors like Zora Neale Hurston and Paul Lawrence Dunbar, I felt proud that even though they were published authors they didn’t release their dialect and made it accessible to their community who spoke the language, and for me, that felt like home. It felt as if their work, in some way was dedicated to my community as a Southern Black woman and those who came before me.

“I will remember, when I was taking a course in public speaking, and, and creative writing at a junior college, Wilson Junior College [Chicago, Ilinois], and--so, I was the only black student in the class and so they were--the teacher was making her assignment about what piece of literature a person was going to read in poetry, and then she assigned me to Paul Laurence Dunbar.Well, he wrote in what they called "Negro dialect". I said, "I can't read--" because I couldn't--you know--you, it's a skill that you have--I mean you have--to write it as well as to read it, so I (laughter) but she just decided--she assigned me that because she felt, well, I should be--maybe that's the way I speak, but I--but anyway.”

I love that she recognized the Black dialect as a skill. That it is. Then, she was asked:

“Do you think it’s important for people to write in dialect?”

To which she responded:

“If, they are writing from experience. If they are writing from experience having heard this--you're putting down exactly. You don't have to--it's like, you don't have to butter it up or make it so it sounds (unclear). If that's--but a lot of things we cannot really write down because--you'll say, or someone'll ask you,"who do you think so and so, did such, and such a thing?" and you say, you'd say, "I don't know," and a lot of the kids say, "I'uh'no", now if you try to write that, I don't think I could--"I own' no", that's something that's--but there are people who like Laurence Dunbar, who will capture, he must have heard people speaking, because he wrote this thing about this about--this story about--a party, my brother introduced me to that, and he said, "Oh, chile I went to a party--." Well, this is the way people who spoke and, and, the people, common people”

- Ella Jenkins

Her views about the Black dialect intrigued me immensely, so I began to explore “Southern dialect.”

When exploring the stories of Southern dialect I came upon Monique Davis’ take on the matter. Monique Davis, a Chicagoan educator politician told the story of many African American people pursuing a field in education, who have turned away because of the racist prejudicial strategies housed within the Chicago School System.

“Well, for years in Chicago, they had an oral examination that would eliminate African American candidates in the oral interview because they had southern dialects. And those who were doing the interviewing felt that a southern dialect was objectionable. So they would make those particulparticular ar teachers, what they called FTBs: Full-Time Basis substitutes. Eventually those walls came down because of people fighting against such behavior. The Chicago Public Schools have been known to have different types of racism at different periods of time. We went through a period, I felt, when [HM] Dr. Manford Byrd was a superintendent [1968 to 1990], in which a number of African Americans were able to use their talents and their skills and actually participate in the growth and development and education of children in Chicago. “

- Monique Davis

Louis Dodd, insurance executive and educator, talked of his experience with the Chicago Board of examinations and the elimination of many African American candidates at the stage of the oral examination.

“Well, I started as a certified teacher. I took the exam right away. The issue though is that though you passed and many people passed the eight hour exam, could not pass, Afro Americans could not pass the oral. And the oral was always done with white persons who would be on the oral exam board. And they were very cognizant to be sure that you had what is called a Midwest dialect, that's the Indiana dialect at that time, that's what they were looking to. And if you had a dialect other than that and meaning that a southern dialect or any other dialect, you would be unlikely to pass.”

- Louis Dodd

But the discrimination towards Black/Southern dialect didn’t stop there, even within the Black community, the way someone spoke was judged harshly, then ensued the respectability politics and the proximity to whiteness as it pertain to someone’s vernacular.

Orlando Taylor, academic administrator, professor, and the man who coined the term “ebonics” spoke on the apparent prejudice within the Black community, between Northern and Southern “blacks”.

“I was aware of going to Hampton [Institute, now University], how Northern blacks would tease the Southern, more Southern blacks with us at Hampton who pronounced words in a way that they thought was different.”

-Orlando Taylor

When growing up in a mixed community, the term “ebonics” was used as an insult. It was sued as a means to tear someone down for their vernacular and used as a way to insult someone’s intelligence or ability to speak so to see that this term came from a place of pure intention was refreshing, to say the least. Ebonics realistically was something I was never consciously ashamed of but was something I was indirectly taught to “code switch from”. So to hear educators speak so eloquently about the language was affirming.

Adelaide Sanford, education administrator, and elementary school teacher talked about her experience with the pushback she received for embracing ebonics and what ebonics meant to her.

“The children come speaking Ebonics. But every language system that a child brings to school should be respected as a language system. You don't condemn it because language is full communication. There's no language that's superior to any other language. That's all I ever said about Ebonics. But when the issue came up about my running for the Chancellor of the Board of Regents, they dragged this out and ran this article in the paper saying that I was a supporter of Ebonics--even had a manufactured picture of me with a sign that said Ebonics. But I have never taken a public stand about Ebonics because to me it's, there's no need for a public stand. Whatever language a child brings to school, you validate that language. Children don't just have to speak one language. Right. When you go to Curacao or other parts of the world, children speak four or five--they come up and say, "What language do you speak?" And whatever it is, they can speak it. So we don't have to discard one language. And then, as I pointed out, the spirituals are in Ebonics. The slave narratives are in Ebonics. You expect me to throw that away.”

- Adelaide Sanford

So how does cornbread relate to the Black dialect? They, to me both represent culture and familiarity. They’ve both found their way to the contemporary world even through respectability politics, racism, and the scoffs and stares from the self-proclaimed “better”. The two represent skill, mastery, and exclusiveness.

Remember: You can’t eat everybody’s cornbread and everybody can’t speak Ebonics.

Digital Archive Playlist:

https://da.thehistorymakers.org/stories/6;IDList=136577%2C360145%2C177880%2C438416%2C78610%2C640892%2C9029%2C444354%2C57430%2C13968%2C12898;ListTitle=Cornbread%20

Topics Searched: Cornbread+ Southern Dialect + Ebonics